Taking Ozempic, Gaining Control & Being Broken

Three years of the moral dilemmas, the eating disorders, the shame, and the newfound clarity.

Trigger Warning: Eating Disorders. This story addresses experiences with disordered eating and discusses clinical eating disorders.

My stomach was in tons of pain — the kind that makes it so you can’t stand up straight without feeling dizzy. I was irritable to the point of not just rudeness or curtness, but meanness. I’d spiral from bouts of chaotic energy to low imperceptible hums. My head generally felt like it was trying to jump out of my skull. I wasn’t sick but I wasn’t well I’d chewed and spit an entire bag of peanut butter cups out, trick-triggering processes in my body that caused all the aforementioned symptoms.

It was always something like that. The kind of things that would pass as watercooler talk and chuckling, “I ate so much last night,” I’d eaten a bag of chocolate chips. An entire batch worth of cookie dough. I’d thrown up because I ate so much then figured I had “accidental bulimia” so could do it over again. This was my natural relationship with food, however unnatural it may seem. Always sugar. Always without moderation or control. Not an eating disorder on paper, but disordered eating. It’s a recognized “thing” but not a diagnosis, and doesn’t adhere to the standards of anorexia, bulimia or orthorexia.

When food becomes an addiction or a compulsive activity, you feel like a puppet. Somebody is pulling your strings. There are cogent thoughts about how continuing this destructive behavior is bad, yet you continue to feed yourself. You know it will make you sick and wretched, but right now it feels so good. There are worse addictions, of course, but they’re all the same beast in different clothes.

Mornings were always the same. Wake up, look in the mirror. Now from the side. Not as skinny as yesterday? A failure, rife with self-hatred. The rest of the day was a wash, spent avoiding mirrors or building reflections. Dysmorphia, compounded with disordered eating is an absolute mindfuck of the greatest order. Who knows when it truly took root. I could detail specific moments of humiliation or teasing spanning back to childhood and up to adulthood. But I won’t. I don’t like to go there because it’s dark and sad and people can be very cruel.

I exercise to a near-religious degree and do what I can to keep my body in working order. I am stronger than most people I know. I do not have Diabetes, but it’s not hard to see disordered eating habits lead to it. My grandfather had it. My estranged extended family had it. My mother has it. My mother is on Ozempic.

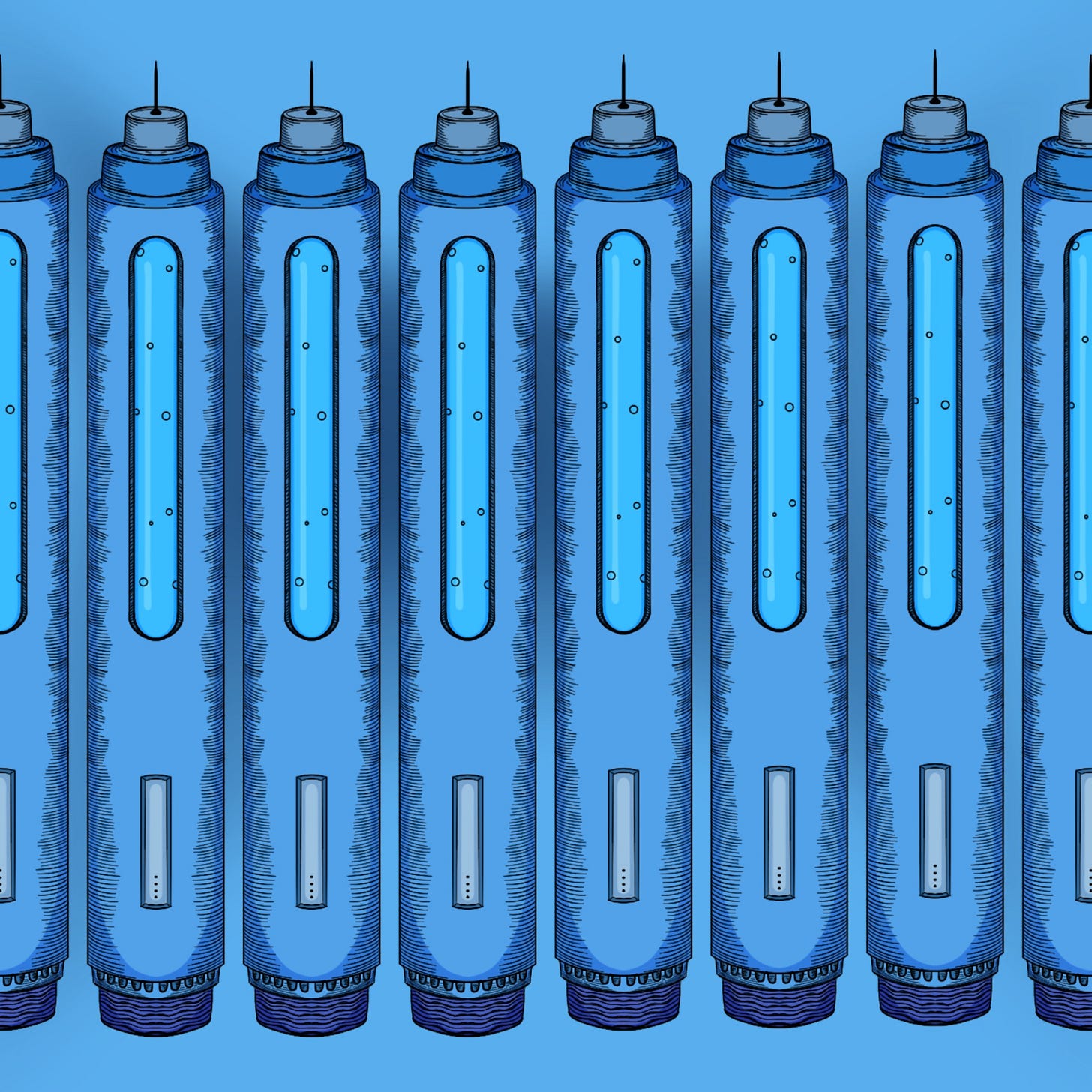

People would tell her she looked great as her frame shrunk. She’d tell them “thank you, I’m sick.” (This is the dark humor our family thrives on.) The dysmorphia in me was drooling for it. This was back in 2021, where Ozempic as a cosmetic was much more of a “secret” than it is today. (It was not in short supply then.) It was easy to get a prescription via shady telehealth services and my insurance covered it. $30 a month for the fabled injection. (Again, this is a while ago.)

It did what it does. But its overall effects were not what I had anticipated. Seemingly out of nowhere, my psychological relationship with food changed. There are no psychoactive ingredients in semaglutide medications, but this phenomenon has been referenced by hundreds of users. Seemingly overnight, I felt control over food like never before. I began to understand what a stable and healthy relationship with it should be like. It was eye-opening and made me feel like a new person. Was this how everybody else lived?

There is a moral implication with Ozempic and its cousins. Anybody who has heard of it knows that it is developed and used to treat Type 2 Diabetes. It is not approved for weight loss. In the past year or so, it has become much more readily available — to the point of multiple brands advertising generic versions in the subway. Still though, how does one morally square using it when there are widely-reported shortages and the people who need it can’t get it?

Well, simply put, I couldn’t. So for a while, I just didn’t take it. I don’t begrudge people who did, because willingly avoiding a drug that gave my life balance in that way seems like a wild thing to say in retrospect. When I would stop and start, my appetite returned and unhealthy habits kicked in, as expected. Novo Nordisk, maker of Ozempic, says it will remain in limited supply until 2024. These days, with various compounds and versions easily available, shortages seem to be less of a concern. I have been on it for the better part of three years and am currently taking it.

My life on Ozempic has been markedly better. There’s the control element as it relates to disordered eating, but there’s also just control in general. And yes, the weight loss was pretty staggering at first, which was initially why I hopped on it. But now, it’s sort of a “come for the weight loss, stay for the overall sanity,” situation. (I still lift weights regularly and do cardio regualrly. Aside from a brief period of surgery recovery, I always have.)

As for my relationship with food — it’s comforting to know that this drug helps quiet my cravings that would give way to blind binging, but it isn’t a cure-all. There are psychological and emotional factors at play that these chemicals can’t touch. Brains are weird and complicated and meant for licensed professionals.

Eating disorders (and disordered eating habits) are considered mental illnesses. They are often imperceptible to the eye and can present in any number of ways, indiscriminately. While I and others have felt better via semaglutide drugs, they can also be incredibly dangerous for diagnosed eating disorders. It’s not hard to imagine why — somebody desperate to lose weight at any cost to themselves could easily abuse it. They almost certainly already are.

Culturally—whew, culturally—the wide availability of these drugs has also proven that we are a culture and society that rewards thinness, despite strides made for body positivity in recent years. I’ve known it since the first time I lost noticeable weight. I was suddenly popular and well-liked and things felt different. Rooms were places to be rather than places to hide. It’s an indelible lesson to a 17-year-old that’s recurred countless times, exacerbated by having a career in fashion, surely. It goes without saying that the pervasive beauty and aesthetics standards shown — which felt extreme in the 90s — played an enormous role in shaping my psyche.

For now, this is something I can do to make me feel better. To make me healthier. To help keep me from blacking out in a mountain of sugar and endangering myself in the process. I’ve been shamed for taking it plenty, but mindless shaming is a small price to pay.

I am not a doctor. This is not medical advice. If you want to speak to a doctor about this or any medical struggles, please speak to your primary care physician. If you are struggling with eating disorders, visit the National Eating Disorders Association for lists of treatment centers and hotlines in your area.

If you are experiencing suicidal thoughts or a mental health crisis, call or text Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: 988 or text Crisis Text Line: “HOME” to 741-741.

I’m a therapist, and I’m really interested in seeing what research emerges on the psychological effects of semaglutide drugs (if possible to untangle from the psychological shift that happens when you see how differently you get treated based on body size.)

We don’t often get to hear from men (making an educated assumption about your pronouns!) about their struggles with disordered eating—this is a good reminder that living in a society that venerates thinness is pretty toxic for everyone, not just women. Thanks for sharing, and happy that it’s been so helpful for you 💙

thanks for putting this out in the world man :)